284: No Objective Truth

Fixating on who's right in an argument doesn't work - there are always multiple valid perspectives

There's comfort in the certainty of knowing that you hold the correct view. The objectively right one.

But when it comes to human perception and interpretation—especially in interpersonal situations—objective truth is far more elusive than we think.

In my work as an executive coach, I often help facilitate conversations between two founders who have been in a fight or disagreement. They're often convinced the other person is wrong about something important.

Maybe there's a past event that they recall or interpret differently. Or a choice that seems obvious to each person should go a particular way.

Most conflicts between people are never purely about "just the facts". Instead they are about perspective, interpretation, and meaning-making. In that realm, multiple truths can coexist.

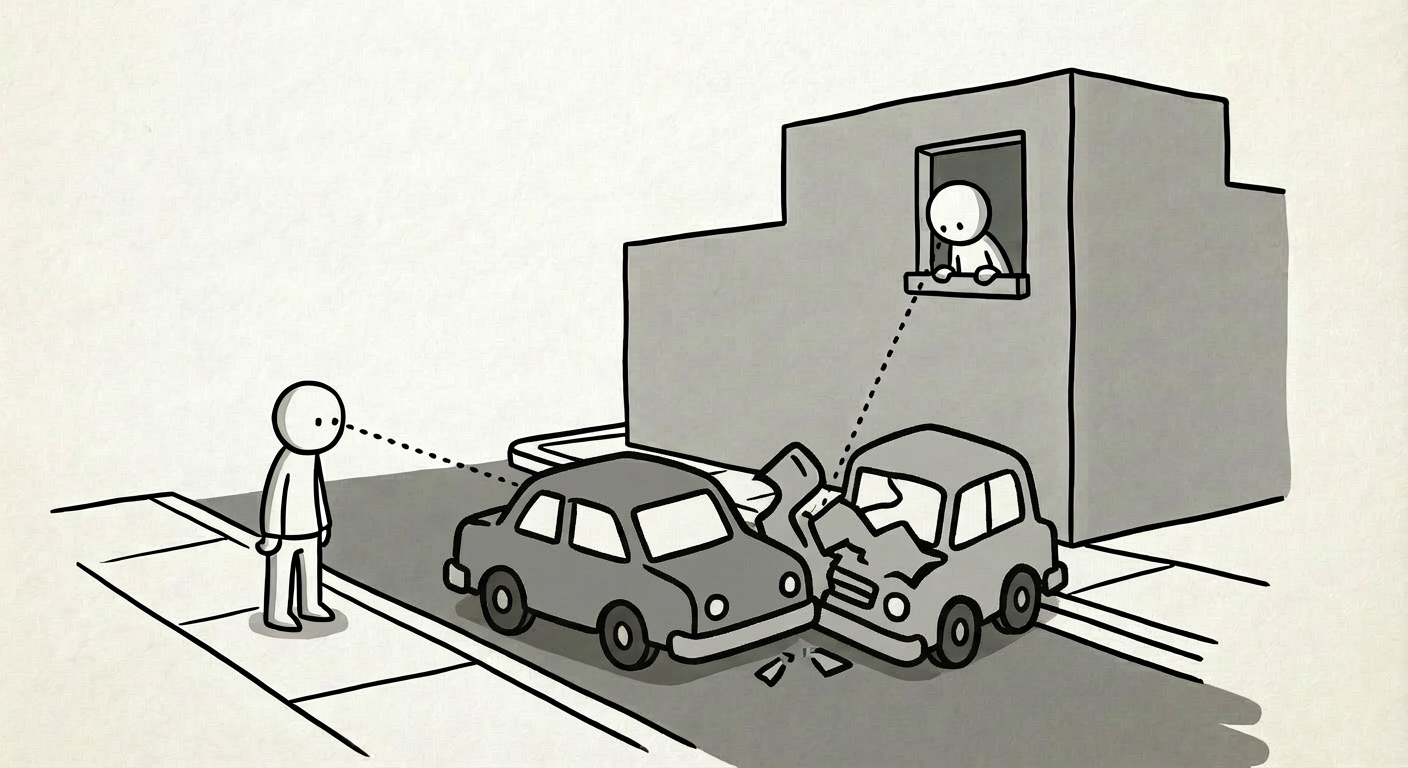

Let's begin from a physical perspective: two people might see the same event but from different angles. Of course their perception of it might be different.

Even when looking at the same thing, we can interpret it in different but valid ways.

The rabbit / duck image is a great example. You can see both a rabbit or a duck depending on how you interpret the image.

Or a chromatic adaptation issue like the black & blue or white & gold dress that consumed the internet for weeks in 2015.

Or those optical illusions where we see the same exact swatch of color appearing to a dark or light shade depending on the pattern around it.

This kind of perceptual ambiguity exists from an auditory lens. In the Laurel vs Yanny debate, people would swear up and down that their version was correct. This video suggests it has to do with our ability to hear higher frequencies (which declines with age), again demonstrating that we can literally miss certain signals while experiencing "the same thing".

People can be primed to hear different things based on what they see. So the same sound can be interpreted as "da" with one set of lips and "ba" when heard by itself—a phenomenon called the McGurk effect.

What we know can also impact how we interpret things.

Once you know how to read, you cannot see words or letters as mere shapes and patterns. They instantly have semantic meaning. Yet show those same words to someone who can't read that language and they appear like abstract marks.

That's because on a biological level, what we see and hear doesn't arrive unfiltered. Our eyes convert light into electrical signals that our brain decodes and reconstructs into what we perceive as sight. Vision isn't a camera recording reality. It's your brain constructing a useful model from fragmented data.

Our past experiences, cultural contexts, and even what we've been told to expect all shape what we perceive. Have you ever drank from a cup that contained something different than you expected? That initial shock was your expectation not matching reality.

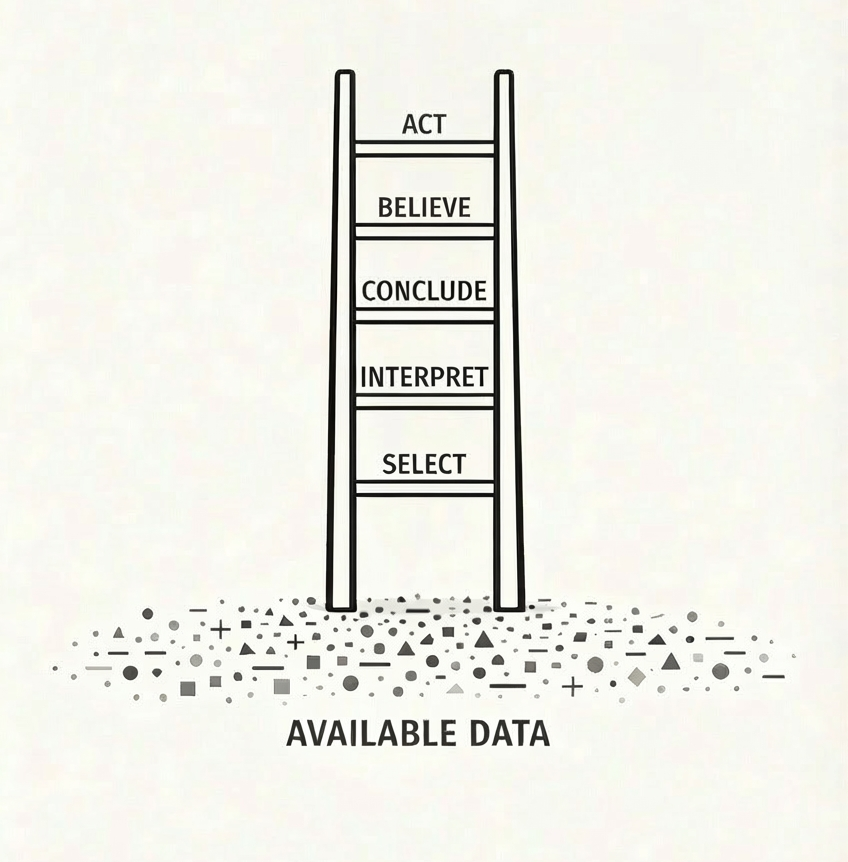

And we've only been talking about single images or sounds. Real-world scenarios are far messier. As mentioned in issue #260 Fraught Conversations, the ladder of inference shows how we build conclusions from selected data—and we rarely all have access to the same data.

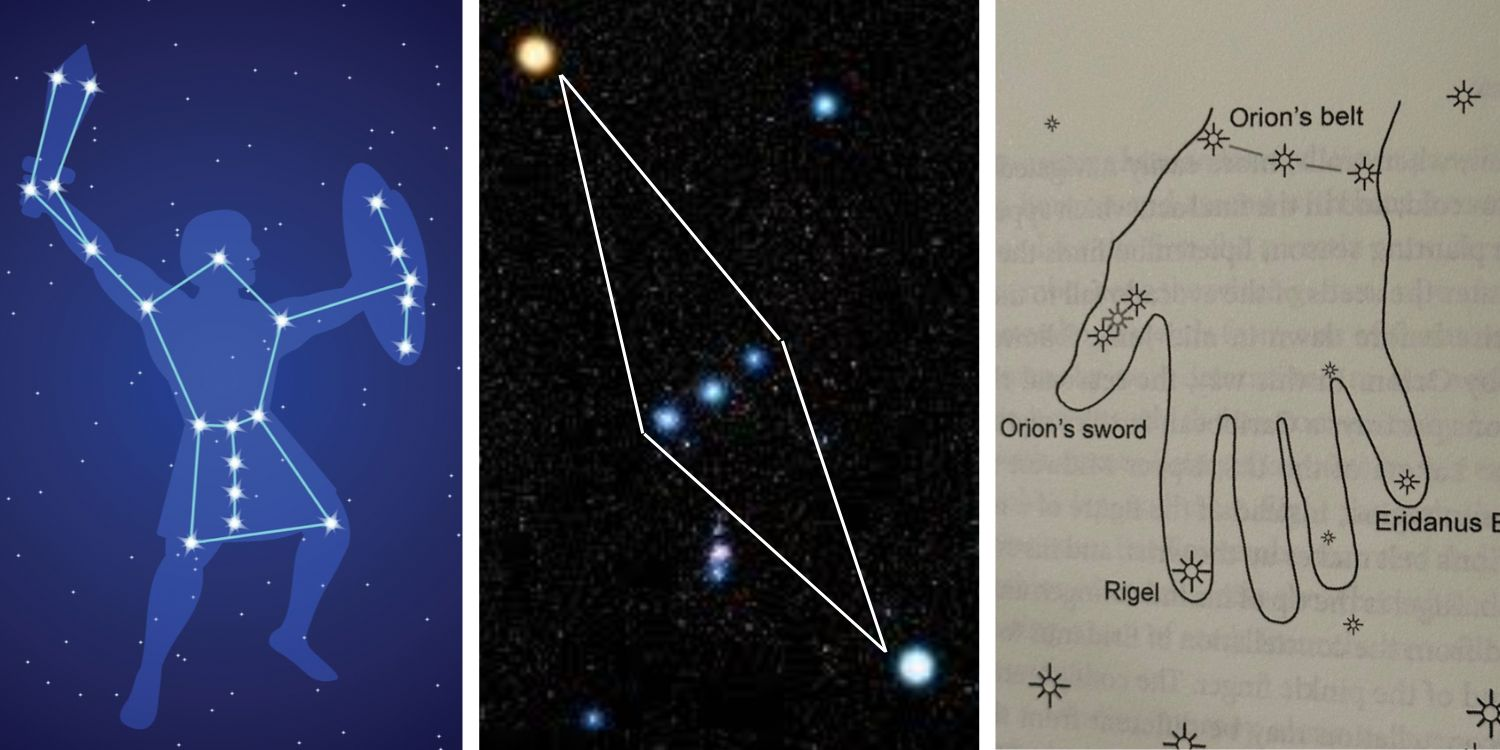

The more data available, the more reasonable conclusions can be assembled. Like how different cultures saw Orion's stars as a hunter, a canoe, or a hand depending on their stories.

Every day, millions of informed traders look at the same stock data and reach opposite conclusions about whether to buy or sell. If they can't agree on publicly available information, why should we be surprised when you and your business partner disagree about the company's direction?

We're also biased by personal history and immediate context. If you were bitten by a dog as a child, any barking dog feels threatening. If you were cut off in traffic before work, a neutral comment come across as an insult. Telling someone "you can't be scared of that cute puppy" is moral judgment (you're a coward), not a factual statement (your fear is not real).

So what's my point?

Yes, mathematical proofs and scientific measurements can have "correct answers" based on agreed assumptions. But most daily conflicts aren't about planetary trajectories. When you're arguing with your spouse about whether they were "dismissive" at dinner, or with your cofounder about whether a project timeline is "realistic," you're not in the realm of objective fact. You're navigating interpretations, feelings, and subjective experiences.

Believing the other person is objectively wrong makes entrenched conflict inevitable. You signal disrespect for their judgment and show no empathy for their experience, which creates defensiveness. Now you've both dug your heels in, because who wants to admit they were incompetent or immoral for thinking what they thought?

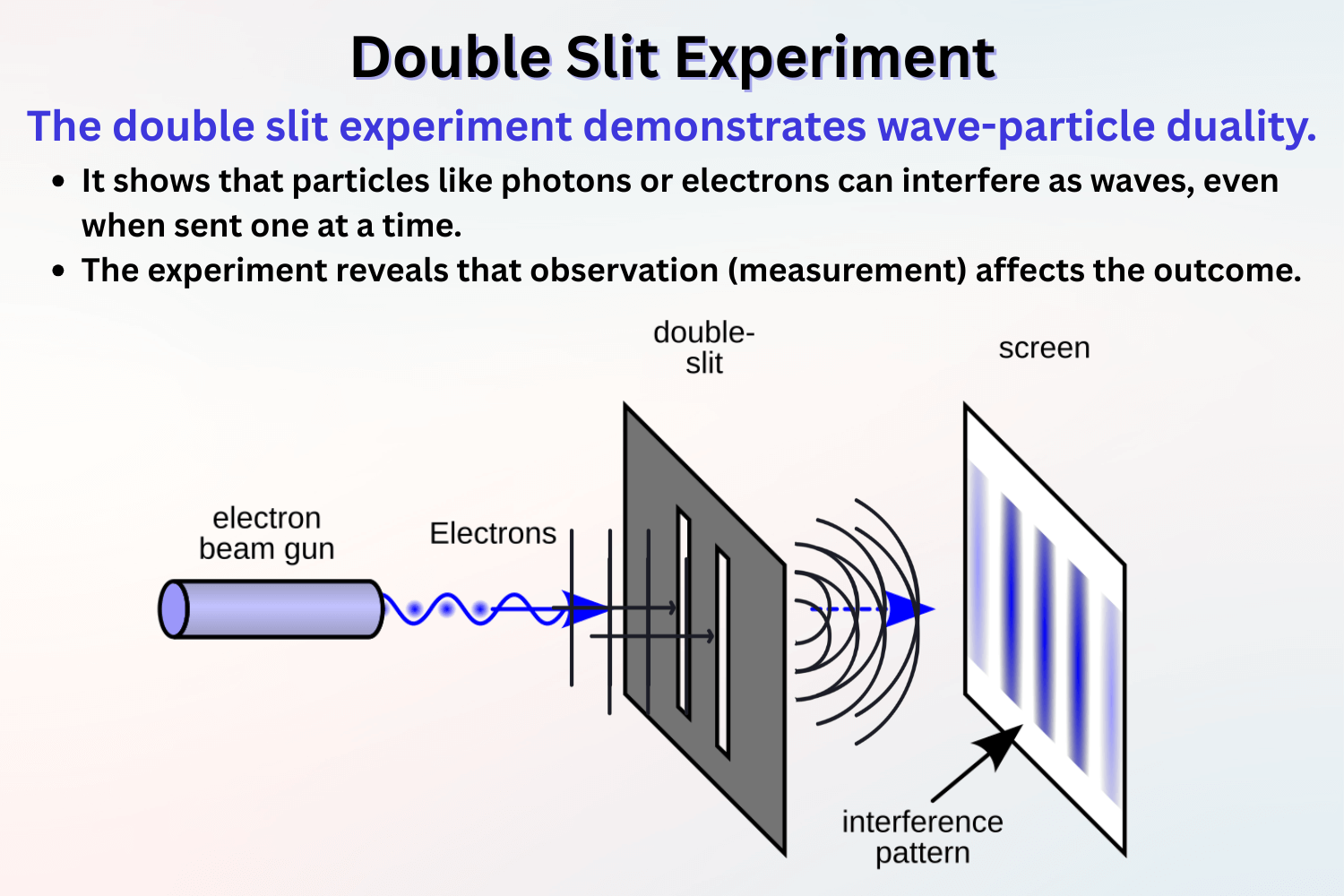

Consider: even light itself behaves as both wave and particle depending on how you observe it. If the most fundamental element of perception can exist in multiple states simultaneously, why should we expect human interpretation to be any different?

The moment you accept that your "objectively correct" view is actually one of many reasonable interpretations, you can get to understanding and empathy.

This requires receiving new facts and new perspectives. When two parties feels the other has empathy for their point of view, their positions softens and they are much more likely to compromise and collaborate. The final working agreement you come to is rarely the position you started with.

Like light itself, every interpersonal situation contains multiple valid interpretations. The question isn't which one is correct. It's whether you can hold space for more than one to be true at the same time.