🖼 Return to Office (Scotch & Bean) + 👉 Koreans Were Boozing Hard in 1020 AD

This the 77th edition of Cultivating Resilience, a weekly newsletter how we build, adapt, and lead in times of change—brought to you by Jason Shen, a PM, resilience coach, 1st gen immigrant, ex-gymnast, and 3x startup founder

🧠 Collaborative Fund's Morgan Housel on Evolution, Psychology, and Risk

Morgan Housel is a partner at Collaborative Fund but unlike most venture capitalists who were previously engineers, bankers, founders, or C-suite executives, Housel's background is in journalism, having been a columnist at Motley Fool and Wall Street Journal. Though on second thought, I suppose it shouldn't be that odd as one of the greatest VC's of all time was also a former journalist.

What I like about Housel's writing is that while it centers around money and finance, it doesn't center around technical charts, analysis, or financial jargon. Instead, he focuses a great deal on the psychology of money (a series of essays he turned into a great full-length read).

In a series of recent essays, he's explored some ideas at the intersection of signaling, framing, efficiency, and evolution. Here are some of my favorite ideas:

Happiness is beating expectations

In his book on the final days of World War II, Stephen Ambrose writes about a wounded American soldier who’s carried back to the medic tent. He knows he’s going home – his war is over. “Clean sheets boys!” he yells back to his comrades still fighting. “Clean sheets, can you believe it! Clean sheets!” Living in foxholes for weeks caused soldiers to daydream about normal life, and few things tickled their imaginations like the dignity of clean sheets. Not money or status or respect or glory. Just the absolute pleasure of clean sheets. It’s an extreme example of when the outside world ceases to exist and everything becomes relative to an internal benchmark.

In Housel's piece on Internal vs. External Benchmarks, he argues that we probably overindex on external benchmarks, which while necessary sometimes, are not as important as internal ones. As a gymnast I would focus on improving my own performance and average score in a competition, rather than comparing my scores to another athlete. Short of sabotaging their equipment or play weird mind games, there was no way for me to affect their performance.

External benchmarks are hard to unpack

External benchmarks are deceiving because accomplishments are advertised while the ugly, hard, and painful parts of life are often hidden from view.

It’s hard to know how much of some external benchmarks owe their performance luck, which you cannot replicate no matter how smart you are or how hard you try. This is especially true when you’re anchoring to a specific person or company’s success.

Continuing on the benchmarks piece, Housel argues that without more information, it's hard to judge an external benchmark. Someone sold a company for $100M but is that a successful outcome? Depends on the terms, the earn out, how much was invested at what valuation. Without all the details, you can't even know how good it really is, much less decided whether you should be judging your own exits on that basis. So why obsess over them?

Everything looks better from the outside

I guarantee workers at the competitor find flaws in the way their company operates, because they know about their company what my friend knows about his: how the sausage is made. All the messy personalities and difficult decisions that you only see when you’re inside, in the trenches. “All businesses are loosely functioning disasters” Brent Beshore says. But it’s like an iceberg, only a fraction is visible.

Instagram is full of beach vacation photos, not flight delay photos. Resumes highlight career wins but are silent on doubt and worry. Investing gurus are easy to elevate to mythical status because you don’t know them well enough to witness times when their decision-making process was ordinary, if not awful.

In Harder Than It Looks, Not As Fun as It Seems, Housel talks about a friend who thinks his own company is totally screwed up and a competitor firm has it all figured out. Housel cautions against that interpretation as his friend has never worked at the competitor.

In a world where we always need to be promoting something–our products, our job openings, ourselves–everyone is incentivized to only signal success and positivity. Which means we largely see people's #bestlife and rarely their problems, which are hidden out of sight. It's easy to think that everyone's life is amazing and a breeze people their mom's sickness is not posted, their credit card debt is password protected, and their failed workout routine is never discussed.

Even titans feel pain

Occasionally a window into reality cracks open. Warren Buffett’s biography The Snowball revealed that the most admired person in this industry has at times had a miserable family life – part his own doing, the collateral damage of life where picking stocks was the highest priority. Same for Bill and Melinda Gates in the last month. Elon Musk broke down in tears three years ago when asked about the mental toll of Tesla’s struggles. “This has really come at the expense of seeing my kids. And seeing friends.”

Everyone’s dealing with problems they don’t advertise, at least until you get to know them well. Keep that in mind and you become more forgiving – to yourself and others.

Another quote from Harder Than It Looks. In an earlier issue of this newsletter (003), I wrote about the idea that "talent needs trauma" and shared a quote from a 2017 profile on Elon Musk about his traumatic upbringing and clearly unresolved emotional issues. That's not to boo-hoo the richest dude in the world as of Nov 2021, but to say that his life is not all sunshine and roses. Same for the Gates and (first I had heard) Warren Buffet as well.

Most things don't work

The key thing about evolution is that everything dies. Ninety-nine percent of species are already extinct; the rest will be eventually.

There is no perfect species, one adapted to everything at all times. The best any species can do is to be good at some things until the things it’s not good at suddenly matter more. And then it dies.

In Casualties of Perfection, Housel talks about efficiency and evolution. Most businesses go out of business. Most religions, civilizations, traditions die out. To survive is the anomaly and it usually means that whatever you're doing is relevant for the current environment, and is capable of adapting to the new environment.

Innovation looks like wasting time

Psychologist Amos Tversky once said “the secret to doing good research is always to be a little underemployed. You waste years by not being able to waste hours.”

A successful person purposely leaving gaps of free time on their schedule to do nothing in particular can feel inefficient. And it is, so not many people do it.

In order to adapt in a changing environment, we can't only try to be maximally productive in the current environment. If we overoptimize for the now, we will struggle in the new. Which means taking time to think about new things, explore new paths, etc. This newsletter for instance, takes many hours each week and does not currently make any money for me. I could spend these hours working a freelance job or trying to get ahead in my full-time job. But I choose not to.

Leave room for the unknown

Super-efficient supply chains increase vulnerability to any disruption. And history is just a constant chain of disruptions.

We are in the biggest post-WW2 consumer boom and car companies are shutting down production because they’re out of chips. A little inefficiency across the whole supply chain would have been the sweet spot.

Same in investing. Cash is an inefficient drag during bull markets and as valuable as oxygen during bear markets, either because you need it to survive a recession or because it’s the raw material of opportunity.

COVID exacted a toll on just about everything, including, as most of the ecommerce world is discovering, our global supply chains because ships can't dock and unload their stuff fast enough. We have to build in buffer for the unexpected and not dock people or teams when that buffer is "wasted". It's effectively your insurance for when things get ugly, which they always do eventually.

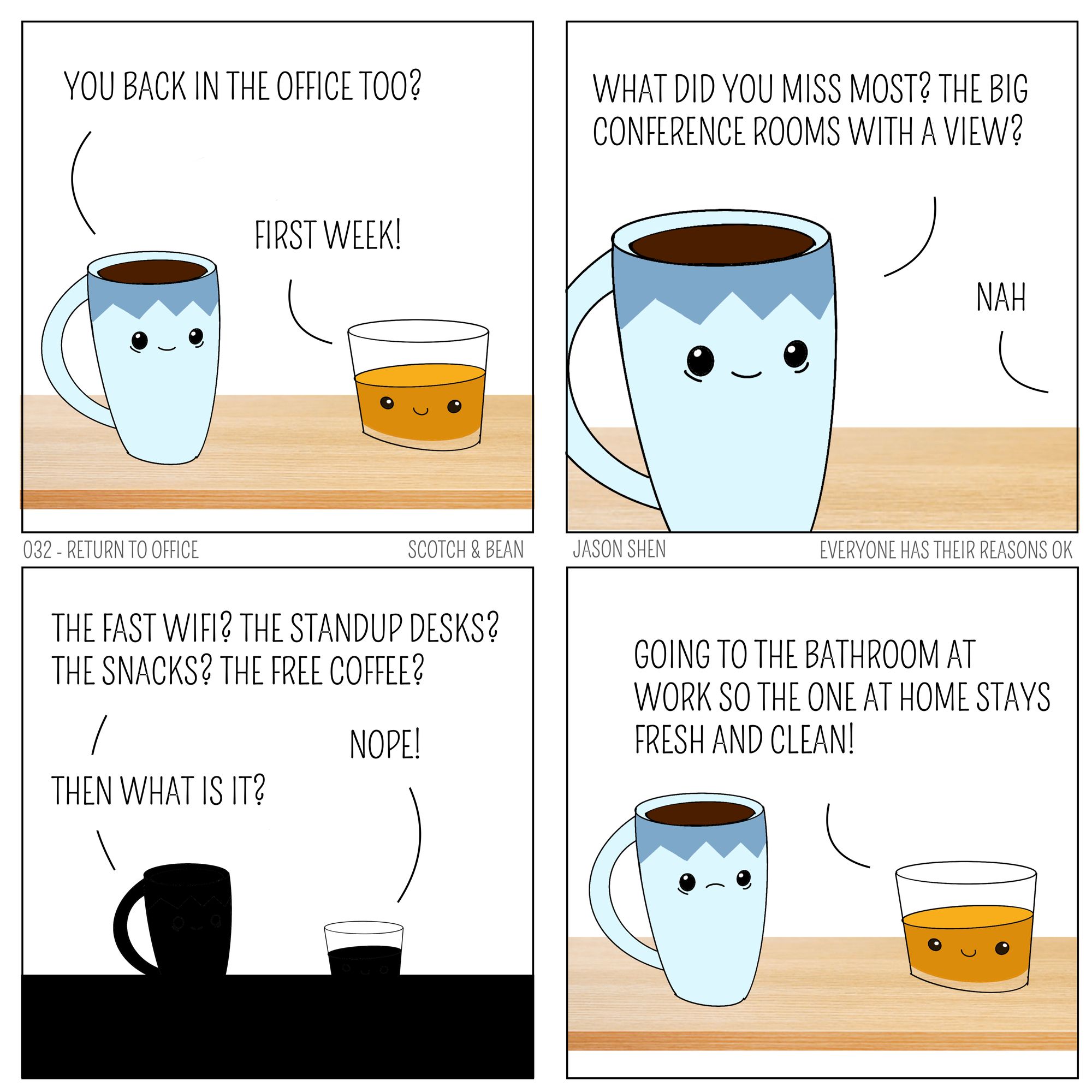

🖼 Return to Office (Scotch & Bean)

For legal reasons, this is a joke. But yeah, there are a lot of other perks executives could be touting for returning to the office.

👉 Koreans Were Boozing Hard in 1020 AD

My new favorite historical artifact is this 1,000 year old, 14-sided die from Korea with instructions for a drinking game 🎲

— Dorsa Amir (@DorsaAmir) October 31, 2021

Known as a juryeonggu (주령구, lit. “liquor command tool”), each side of the die has an action, like “drink two cups” or “dance without music”. pic.twitter.com/UauP0jyiPk

Came across this tweet and found it hilarious. You think frat boys or salarymen were drinking hard? Look at this dice drinking game that's a thousand years old. Human beings really are fundamentally similar, just with more technology.

Like this edition of Cultivating Resilience? Help me reach more people who could use these ideas by sharing it!